Sommaire

What are the major informational changes impacting organisations?

Over the last 10 years, a number of informational changes have had a major impact on organisations and have shaken up the way in which reputation, societal issues and information are managed within organisations. What are these changes?

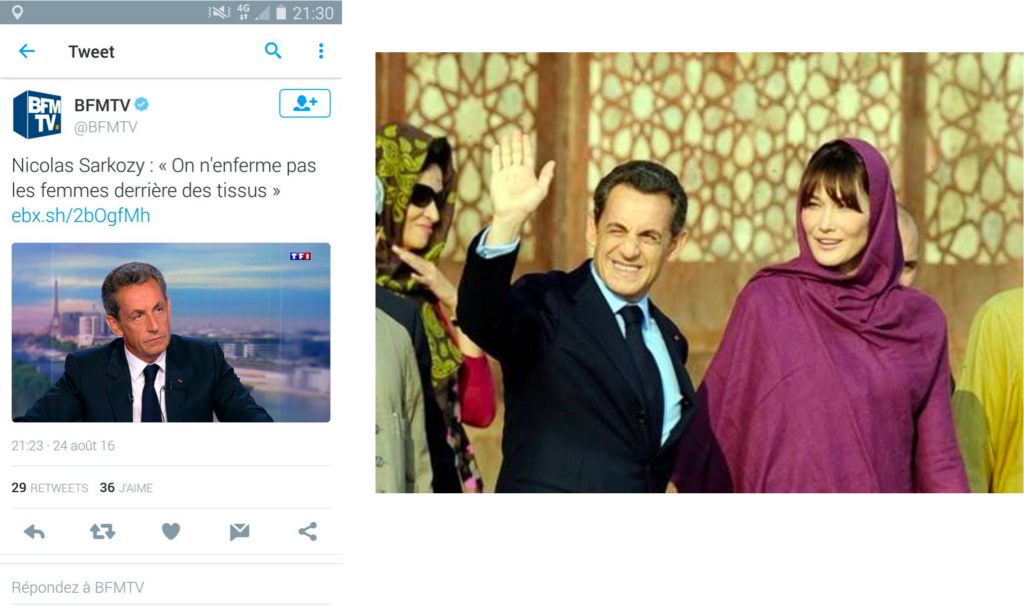

- The rise of digital traces and their impact on individuals and organisations : we produce traces and the main problem with them is that the context in which they are produced is not provided, which means that when someone consults the digital trace, they have a different context at the time of consultation.

- With the arrival of social media, we have all been given an incredible power: the power to publish . However, this power has not been harnessed by everyone in the same way: extreme and radicalised people publish far more than others, so we have an overproduction of extreme content. At the same time, the democratisation of content production has made it possible to produce hyper-niches for ultra-specialised content.

- Everything can be filmed or photographed : with the arrival of smartphones, everyone has become a potential camera. This creates a world where the illusion of reality is present everywhere, whereas a photograph can be framed, put into perspective or contextualised differently.

- Platform architecture : algorithms have created a system with an imbalance of power where organisations do not have access to audiences that are sometimes activated by third parties.

Here, we should see an even greater boom insofar as digital traces can be generated by artificial intelligence. Added to this will be even more videos where the identification of faces and identities will make it possible to search for people in videos on this basis. The illusion of reality will even be able to be faked with the deeps fakes that are gaining in intensity every year. Finally, the explosion in the fragmentation of social platforms will make it impossible for organisations to counter-balance all the discourse (and even to monitor it). (In short, we're in for another 10 years of major informational changes that will transform our profession!

The arrival of digital traces and the implications for organisations and individuals

January 2015: when the names of the terrorists in the Charlie Hebdo attacks are listed, it's easy to see the history.

It's easy to see, without being an intelligence service, that he is on the list of terrorists mentioned in a book on Google book, while an article in Libération shows that he has already been convicted of offences in which he is described as an occasional Muslim because he smokes and drinks.

In the same way, Amedi Coulibaly appeared in an article in Le Parisien in which he is shown to have met Nicolas Sarkozy.

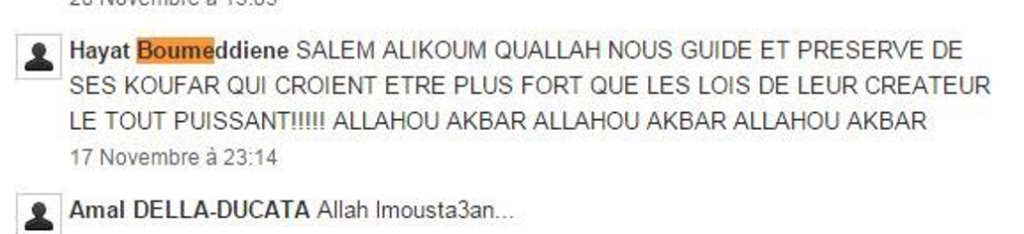

With regard to his girlfriend Hayat Boumeddiene, we can see that there was a very radical comment published, which gives a more or less clear idea of her state of mind.

The great tragedy is that there are namesakes who share their digital identity. Someone is going to receive a lot of negative comments, personal attacks and so on.

This small example shows that as early as 2015, we are able to use digital traces to track down vital information about people whose names alone are released.

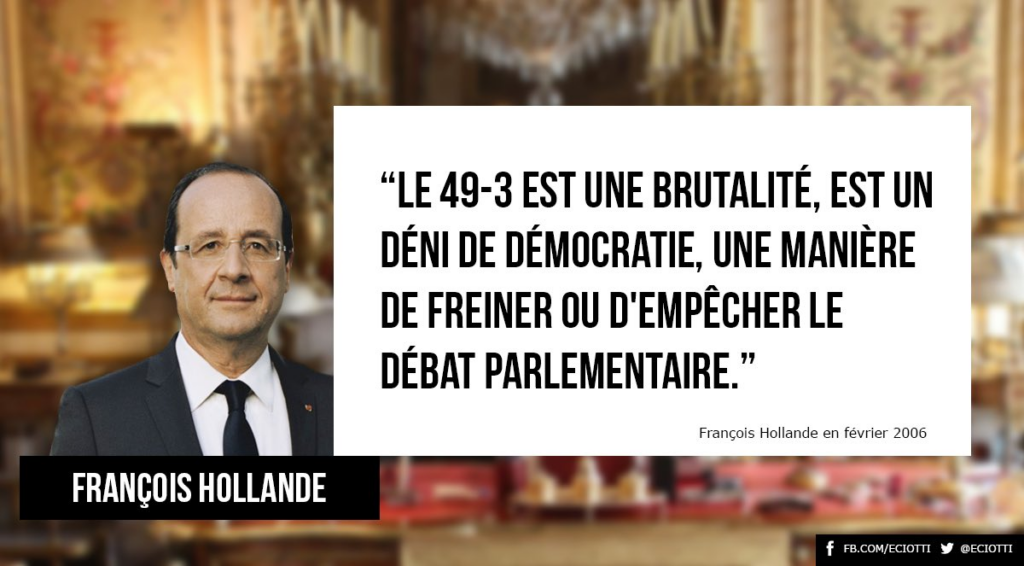

One of the implications of this will be that we will now be able to carry out a historical review and therefore compare two statements on the same subject at different intervals, so we can have a completely different opinion, since the context of production will be completely different from the context of someone's consultation, i.e. when I publish something on the Internet, I'm publishing it in a different context.

This already existed, and one of the most high-profile examples was François Hollande's use of the 49.3, which he criticised in opposition but used to the full once in power.

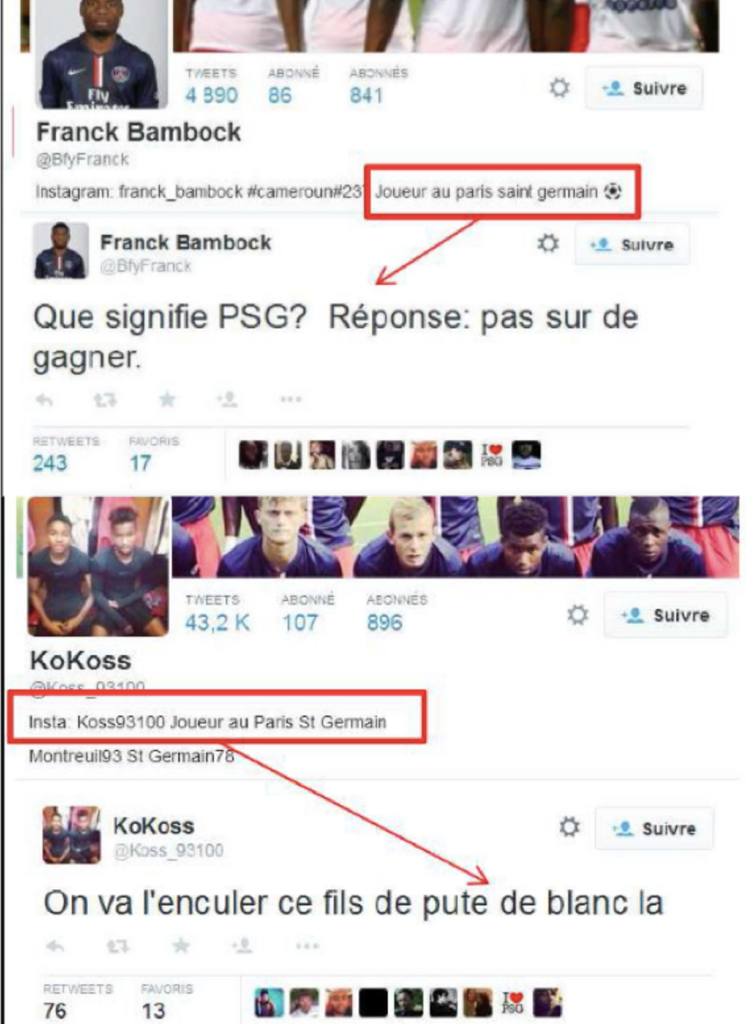

But what changes is that changes in status are even more problematic. A person who is the talk of the town can become the talk of the town. The most illustrative case is that of professional players. There have been a number of PSG players who were teenagers and commented on football on Twitter. Once they became professionals in a Paris-Saint-Germain team coached by Laurent Blanc, Internet users dug up comments about PSG or Laurent Blanc.

Conclusion and major change: It is therefore important to think about your messages over time. There is a difference between the context of production and the moment when people consult what you have produced. The world evolves, as does status, and so the same message can be interpreted differently. So you have to think about your reputation in the long term and anticipate societal changes.

Anyone can become a producer of information: the information market is becoming extreme and specialised.

With the advent of social media, we've all been given an incredible power: the power to publish.

However, this power has not been harnessed by everyone in the same way: extreme and radicalised people publish far more than others, resulting in an overproduction of extreme content. At the same time, the democratisation of content production has made it possible to produce hyper-niches for ultra-specialised content.

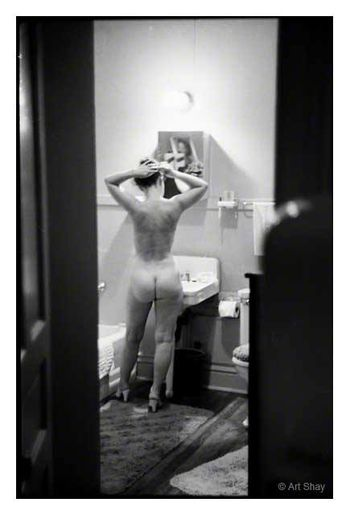

Everything can be filmed or photographed

In fact, we live in an age where anything can be filmed or photographed. When a helicopter from TF1's Dropped crashed in Argentina, we almost immediately had video footage of the tragedy.

This change has meant that employees of organisations have become major crisis factors. The first cases began in 2007 with a Comcast employee in the United States who was filmed by a customer asleep on his sofa while he was installing cable in his flat. Sometimes, it is even the employees themselves who film themselves and broadcast a problematic video, like these two Domino Pizza employees in 2009 who filmed themselves putting boogers in the composition of their pizzas.

The fact is that with the arrival of smartphones, everyone has become a potential camera. With the rise of these new technologies, we are seeing new reflexes. In August 2014, for example, a Mac Donald's customer received her hamburger. She opened it and discovered a swastika on the bun.

- Whereas previously her first instinct would have been to speak to the restaurant's chef, she was quick to photograph the incident and circulate it, alerting the press who were quick to write numerous articles about the incident. While it used to be possible to dispute the version of events, the organisations are now faced with irrefutable physical evidence. The only solution is to bend over backwards and let the storm of unrest pass.

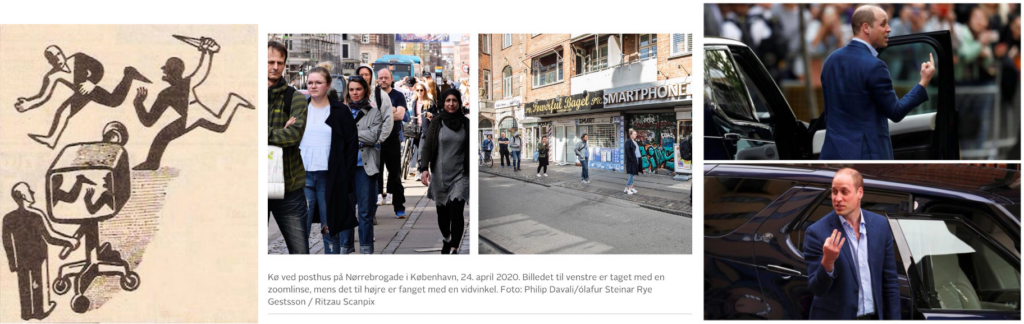

- This illusion of reality has several problems. Firstly, an image or video is framed. So there is an inside and an outside. So you can show what you want to show.

- Secondly, perspective can be used to create a misleading illusion (see the two examples on the right).

- In the case of videos, there is a montage with a before and an after in that we can show a situation that follows on from a previous one that is not shown.

- Finally, sometimes actors can put a photograph and write a context or a story that doesn't reflect reality. If I take a photograph from 2017 that was taken in South Africa, when in reality it's from 2019 and Korea, I can fool as many people as possible.

The imbalance of power

At the start of social platforms, there was a need to automatically prioritise content. In the traditional media, an editorial board defined what information was essential and what was secondary. That's when "like" came into play: if people like content, there's a good chance that other people will like it too. Initially, the idea was a good one, but it led to the emergence of content that was not very informative (chat videos, buzz, jokes, etc.). It also created an imbalance where NGOs could produce huge media volumes (e.g. Kit Kat and palm oil), while companies were unable to bring out the same subjects. (Palm oil) This has resulted in a platform architecture that favours flashy content to the detriment of substantive content.

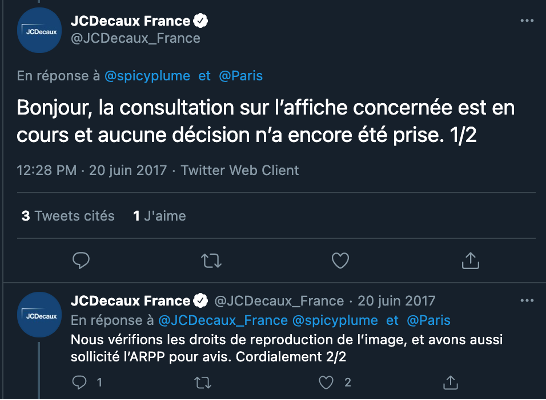

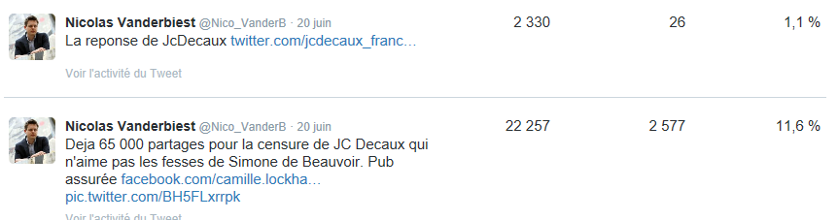

During a controversy surrounding JC Decaux's censorship of an advertisement featuring Simone de Beauvoir's buttocks:

On the same day, within the same original audience, I published on the subject.

The difference in impressions was drastic (2k versus 22k):

This means that if someone says something stupid, untruthful or emotive and it has to be corrected, the whole world will never see it. We're a long way from that, whereas when we had a right of reply in the traditional media, we had much closer correspondence. Organisations are therefore in an ecosystem where the rules of the game put them in a situation of imbalance insofar as even advertising does not necessarily allow them to reach similar audiences.