Sommaire

#SaccageParis: Astroturfing or Activist Operation?

Yesterday morning, on RTL’s morning show, Anne Hidalgo addressed the #SaccageParis campaign on social media, which she accuses of being an astroturfing movement led by the far right. But what’s the reality?

Analysis via Brandwatch

What is astroturfing?

Astroturfing is a communication technique first named by U.S. Senator Lloyd Bentsen. The term comes from a synthetic grass product that mimics natural grass. The senator wanted to contrast citizen-led "grassroots movements" with corporate attempts to simulate a grassroots movement around their cause.

This technique has long existed. For example, Richard Nixon's administration sent letters praising his policies to the "Letters to the Editor" sections, and tobacco companies created fake pro-tobacco support groups. However, with the advent of the Web, particularly Web 2.0, astroturfing techniques have surged, leading to what some call its golden age.

In 2016, I provided a complete guide on what astroturfing is, which you can view here.

Summary of the situation

There is astroturfing to the extent that those who started the phase engaged in abnormally high, unnatural activity on social media. The trending topic was therefore driven by a minority (1,000 people). A tweet published before the launch suggests potential premeditation. However, the controversy stems from Parisians with different political affiliations, not from the far right. Pierre Liscia, who was accused, only appeared after the controversy had already begun. If he isn’t behind @PanamePropre, he can’t be blamed.

Anne Hidalgo is right to emphasize the importance of journalists being aware of these mobilizations' dynamics online. Understanding the techniques is crucial, and during media coverage of online phenomena, journalists should avoid generic terms like "The French," "Parisians," or "internet users." These expressions only represent part of the issue, part of the actors involved, and it is essential to question the facts without hiding behind "French-speaking internet users" as a whole.

What are the key questions?

Let’s first analyze the propagation to gather all the necessary information:

So :

- Firstly, a group of accounts surrounding @PanamePropre initiated the trending topic, using a substantial volume of posts. As we’ll see, the people who propagated the hashtag have diverse opinions, and they are not from the far right..

- Secondly, the trending topic caught the attention of journalists and media outlets like Emmanuelle Ducros, Le Parisien, and Le Figaro, as well as politicians (Marine Le Pen, Pierre Liscia), who only entered after the controversy had spread.

- Lastly, the media amplified the controversy, causing it to grow further, even reaching foreign outlets on Facebook.

Is this astroturfing?

The answer is complex, so I will break it down, as some aspects indeed reflect astroturfing techniques while others suggest otherwise.

YES

Overactivity of certain activist accounts:

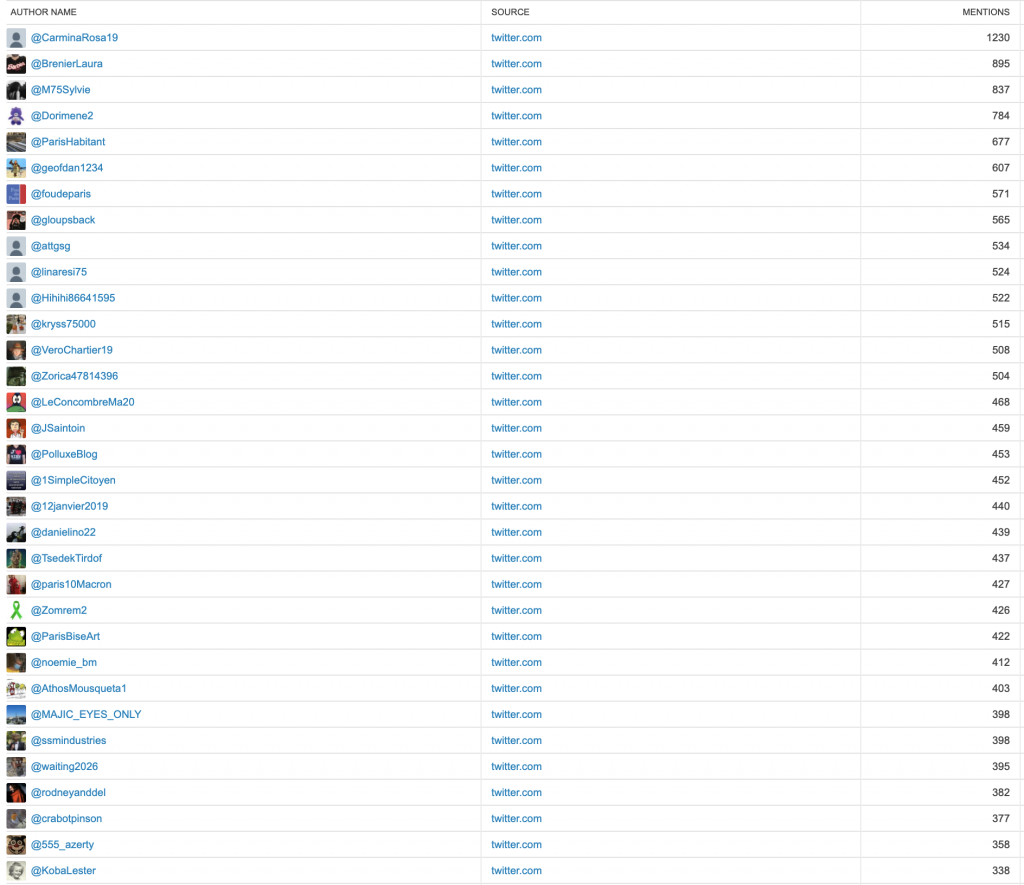

Firstly,a the hashtag was pushed by a number of accounts that were more active than normal. The first account tweeted no less than 1,230 times.

Political intentionality:

It is clear that the campaign is political. In the concept of astroturfing, there is an opposition to what we would call a "grassroots" movement, which is a citizen-led initiative born from local issues. While some citizens may have joined the movement later without any political vision, the hashtag's origin was clearly a political operation. One of the first tweets in the sequence, from a very active account, seems rather odd in this regard:

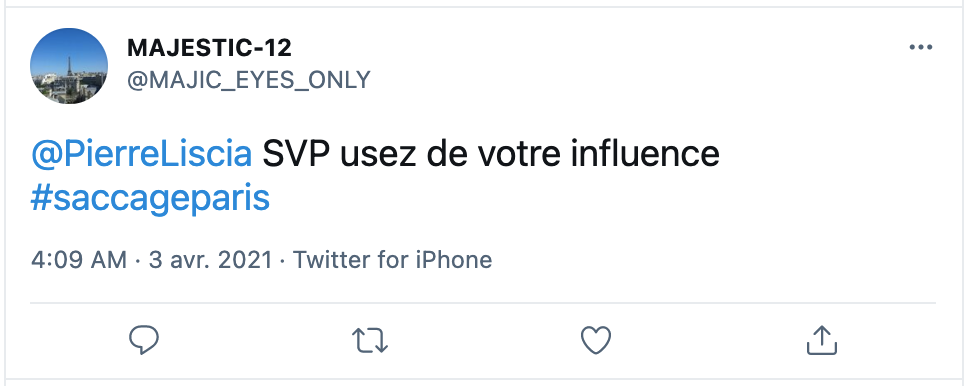

The account that initiated the controversy, ParisPropre (@panamepropre), emerged with the goal of engaging the media, with a political foundation centered around existing movements (Quartier de Lariboisière, La Chapelle, etc.) and around Pierre Liscia.

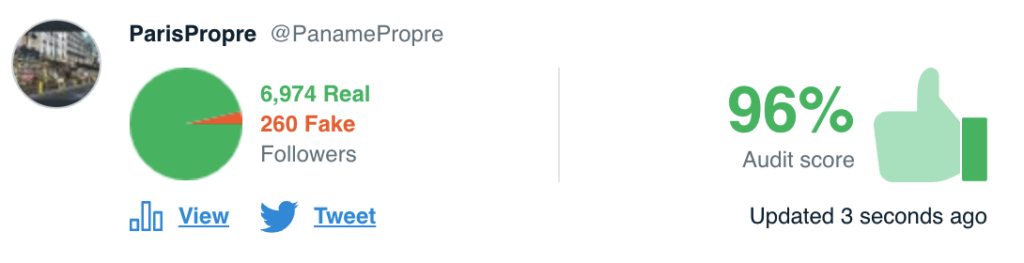

In one month, the account accumulated no less than 7,221 followers.

So, the question arises: Are these followers real or not?

A quick check, though not always perfect but useful for flagging doubts, through, TwitterAudit.

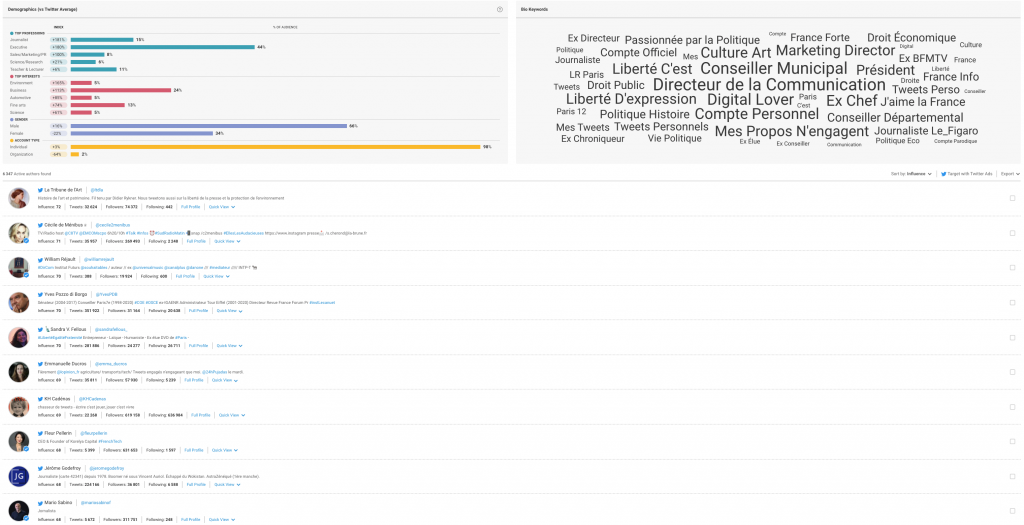

The analysis of followers using Brandwatch Audience shows the same thing: people from Paris, mostly professionals, who "love France," along with a few influencers among the followers.

The analysis of what the followers publish shows that they are mostly opposed to the city of Paris, but not aligned with a particular political side.

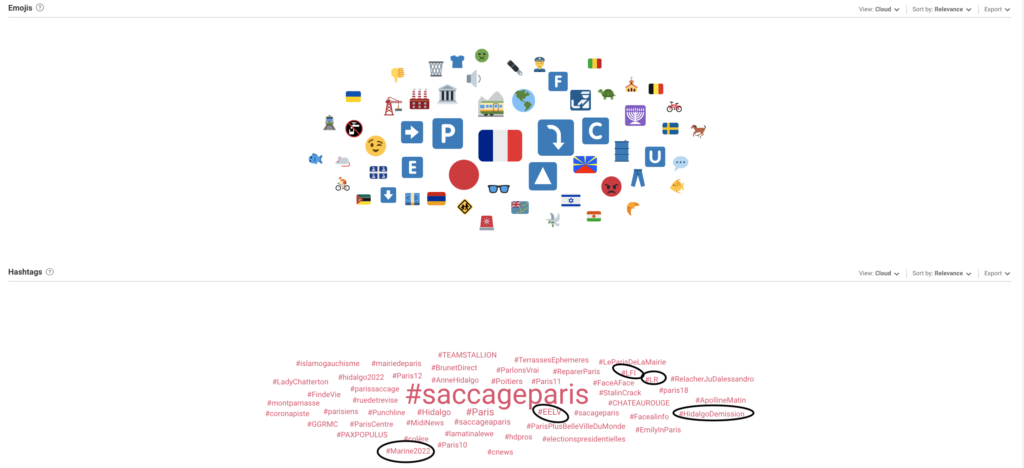

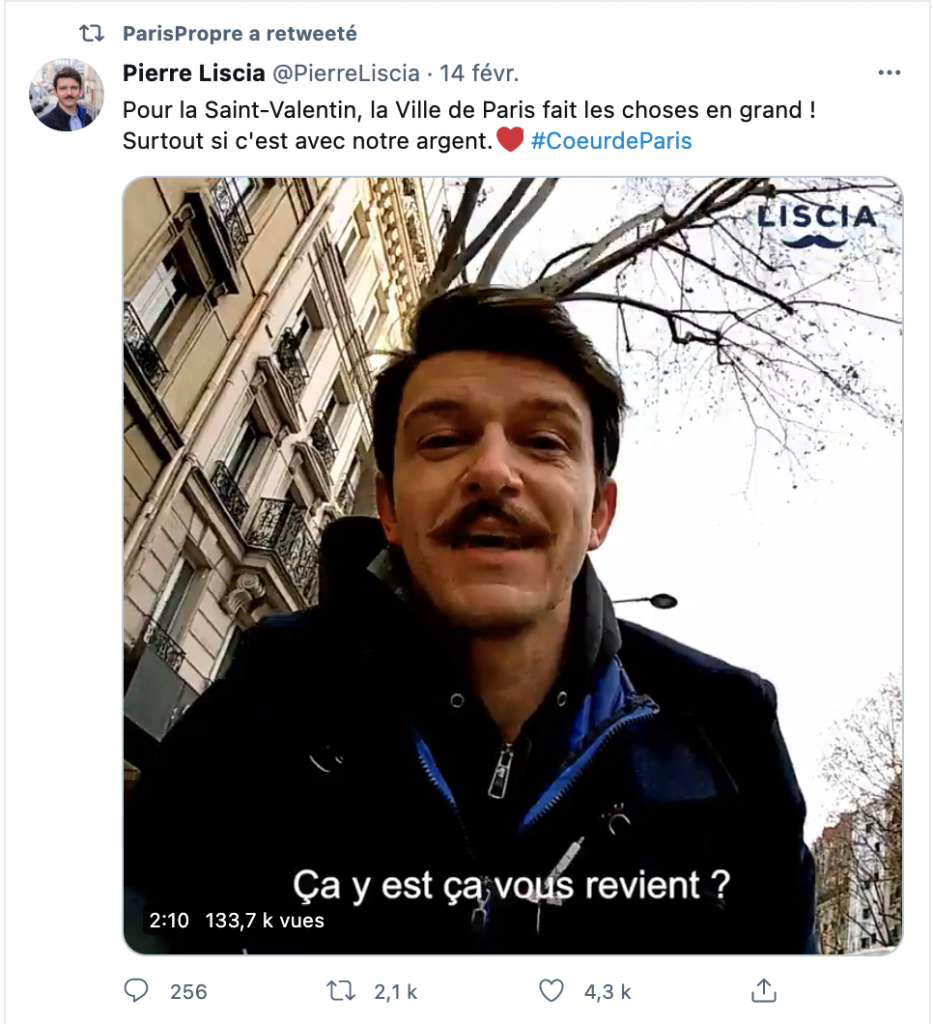

However, the analysis of the domains they share is clear.

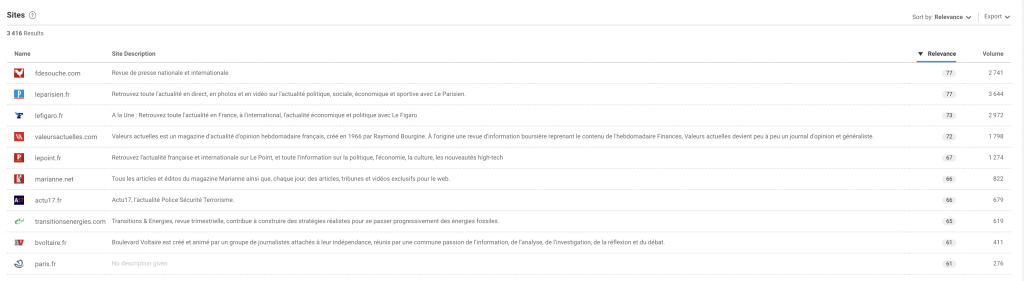

It is notable that outlets like Valeurs Actuelles, FDeSouche (in first place), and BVoltaire are among the most shared, suggesting a clear right-wing alignment. In the early stages of the account, it was very inclined to retweet many of Pierre Liscia's statements.

Connections between different spheres are evident; no new pages were created for the occasion. This shows that, apart from the Twitter-driven campaign aimed at engaging the media and creating a political phenomenon, the issue did not spread widely.

But also, NO

The scale of the super-active accounts remains relatively reasonable:

I always like to look at the share of the 1% most active accounts in the total number of tweets: 218 actors produced 46,894 tweets (out of 134,969 tweets), or 34.7% of the tweets.

This is relatively within acceptable limits. By comparison, during the Benalla affair, 89% of tweets were produced by 1% of the most active users.

The content is genuine:

Beyond slogans, hashtags, and massive retweets, the videos and images are real. They were photographed and filmed by Parisians. The content was relatively scattered, so it's inaccurate to claim that everything is fake or generated by outsiders.

Anonymization of accounts is no more surprising than usual:

Of the 21,836 people who tweeted using the hashtag, only 2,110 used their real names. This is quite typical of conversations on Twitter, especially in the political sphere. Therefore, it cannot be said that this movement is particularly "anonymous" compared to other issues.

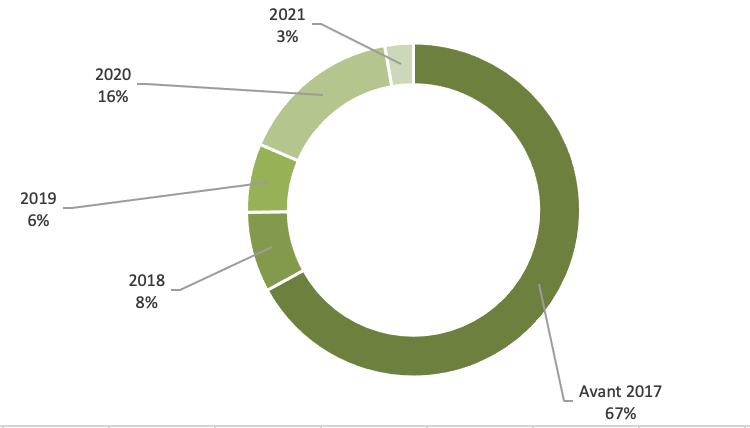

No account creation in 2021:

These are mostly old accounts, with the exception of PanamePropre.

Mobilization observed on Facebook:

n the case of a broader societal activation (like the Black Lives Matter phenomenon, or the ecological transition), we would expect to see the same enthusiasm on Facebook, with public pages targeting people and an ultra-mobilization across all media.

In my initial analysis, I said no. However, by 1 PM on September 9, I received more complete data showing a community dynamic on Facebook.

Does the controversy originate from the extreme-right?

NO

There is no doubt: the controversy does not come from the far-right. While Marine Le Pen may have been present via a tweet, placing her among the top influencers in "press-button" software, she does not hold a central position.

Her involvement is peripheral, with few activists around her statement. That said, when analyzing the followers of the main account spreading the controversy, we find sites like Valeurs Actuelles, FDeSouche (in first place), and BVoltaire, which indicate a right-wing slant. However, not only the followers of this account contributed to the controversy.

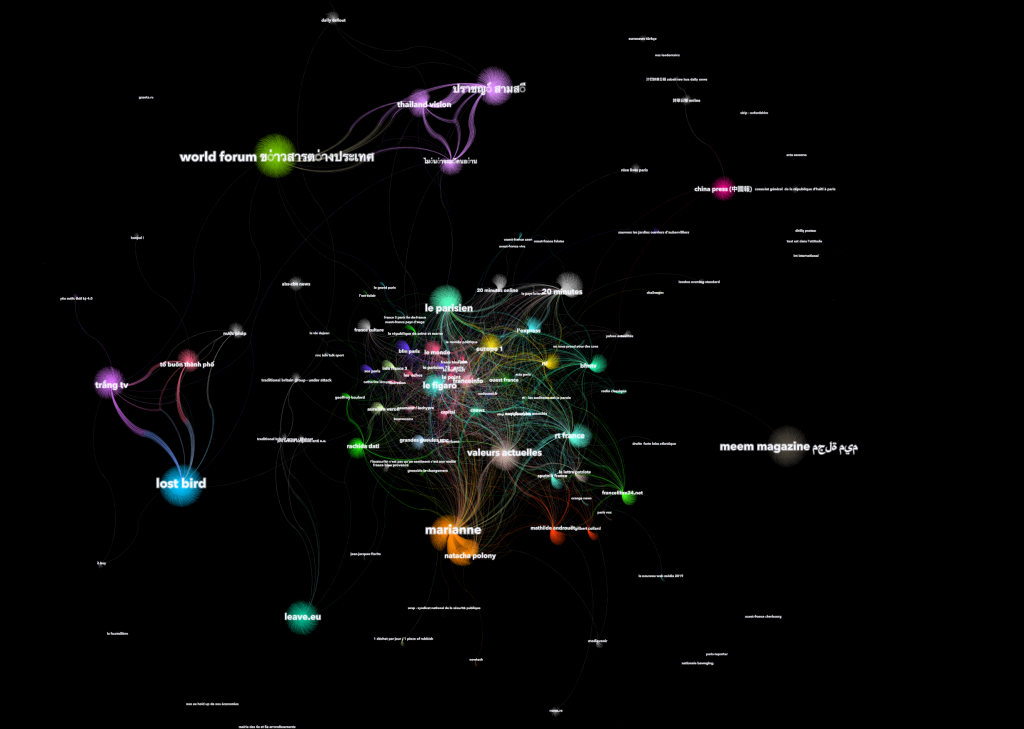

Finally, the last analysis proving this is the study of those who were at the origin of the controversy, from March 21 to April 1, showing three distinct dynamics:

A group of Parisians (in green) starts the controversy. This larger community includes citizens, locals, and individuals who indicate in their biographies that they are on the lists of MODEM or Rachida Dati's lists.

Next comes a community (in blue) with many people who declare themselves as "En Marche" or express support for Macron in 2022.

Finally, a community (in purple) consisting of individuals who describe themselves as "Gaullist," "Pro-Fillon," or "Patriot," including accounts from Debout la France.

Overall, four very influential people in the original network: PanamePropre, FoudeParis, and Aurevoir Hidalgo, followed later by Emmanuelle Ducros.

In conclusion, this is not at all a far-right controversy. It can be said that these are individuals generally in opposition, but they cannot be classified as far-right. There are people who declare themselves in their biographies as Modem, LREM, DLF, or LR, which are opposition parties.

Various circulating social listening platform screenshots showing accounts leaning to the right are accurate, but they only reflect the controversy's later stage, after most of the spread had already occurred. In social media movements, it is essential to focus on the early stages of creation and propagation.

Does the controversy come from Pierre Liscia?

NO

While it is possible to link many of the accounts that spoke out to Pierre Liscia, and he greatly contributed to the campaign, it is impossible to claim that he initiated it. The available evidence does not support this.

For example, a tweet from the early moments.

In fact, in this type of social media opinion movement, it is logical to find networks aligned with the discussed topics. Pierre Liscia has been active in these areas for years. He has gathered a large number of followers dissatisfied with Paris' security and cleanliness policies (drug injection rooms, cleanliness, etc.).

It is therefore logical that a cleanliness controversy would position him as a key figure in the spread. In conclusion, while many of the accounts interacting and following Pierre Liscia are involved, it is impossible to link him to the start of the controversy, unless Pierre Liscia is PanamePropre, as this was the most important account in the spread.

Is the controversy an expression of Parisians as a whole? Are the media missing something?

NO, clearly not.

As is often the case in this type of campaign, it only represents a community trying to assert its rights and opinions to a larger audience. What can be said is that the audience is Parisian, that the audience leans right on the political spectrum, and has always been against Anne Hidalgo, whether three years ago or today.

This is where the danger for the media lies:

Portraying them as representative of Parisians as a whole is a journalistic and factual error. It represents a misunderstanding of this type of awareness campaign on the part of journalists. It is difficult for them to distinguish between a purely "authentic" campaign, astroturfing, or a political agenda. Anne Hidalgo's position on RTL is, therefore, partly true.

However, does the fact that those speaking out are right-wing mean they should not have a voice or that the reality they highlight is false? No. It is authentic, real, and backed by evidence. And the vast majority of those speaking out were not far-right.

The core problem here is that the articles present "Parisians" as a whole mobilizing on social media to denounce chaos. In doing so, they engage in what I call metainformation: they report on a fact not to describe the facts themselves (cleanliness is an issue in Paris, and we have investigated it) but to comment on a metainformation: PEOPLE SAY cleanliness is a problem in Paris. This is the crux of the issue.

The challenge for the media and journalists is to understand these techniques, to avoid speaking in generic terms like "The French," "The Parisians," or "Internet users," but to present the issue as an expression of part of the problem, and to question the facts without hiding behind "French-speaking internet users."