Sommaire

Fast Fashion: the broader the issue, the less progress it makes

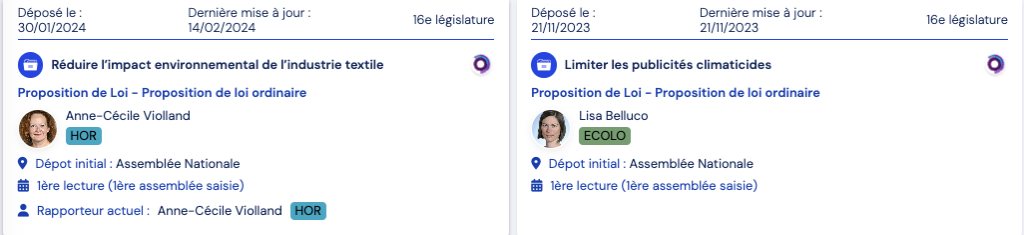

On 14 March, a Horizon bill entitled "Reducing the environmental impact of the textile industry" will be debated in the French National Assembly. Over the past year (even if it all started with the e-commerce boost around covid and the problem could be traced back to Rana Plaza), "Fast Fashion", a term that was little known just a few months ago, has blossomed and the problem is everywhere.

As always when an issue emerges in the public debate, the desire for regulation is strong, especially as the subject is sexy in the media.

And there's plenty to eat and drink in the measures planned: compulsory communication on websites such as "for short journeys, give priority to walking or cycling, think about car-sharing or take public transport on a daily basis"; a ban on certain products; a ban on returning certain parcels; the creation of an "ecoscore / vetiscore": everything is being mobilised and devised.

Regulatory issues

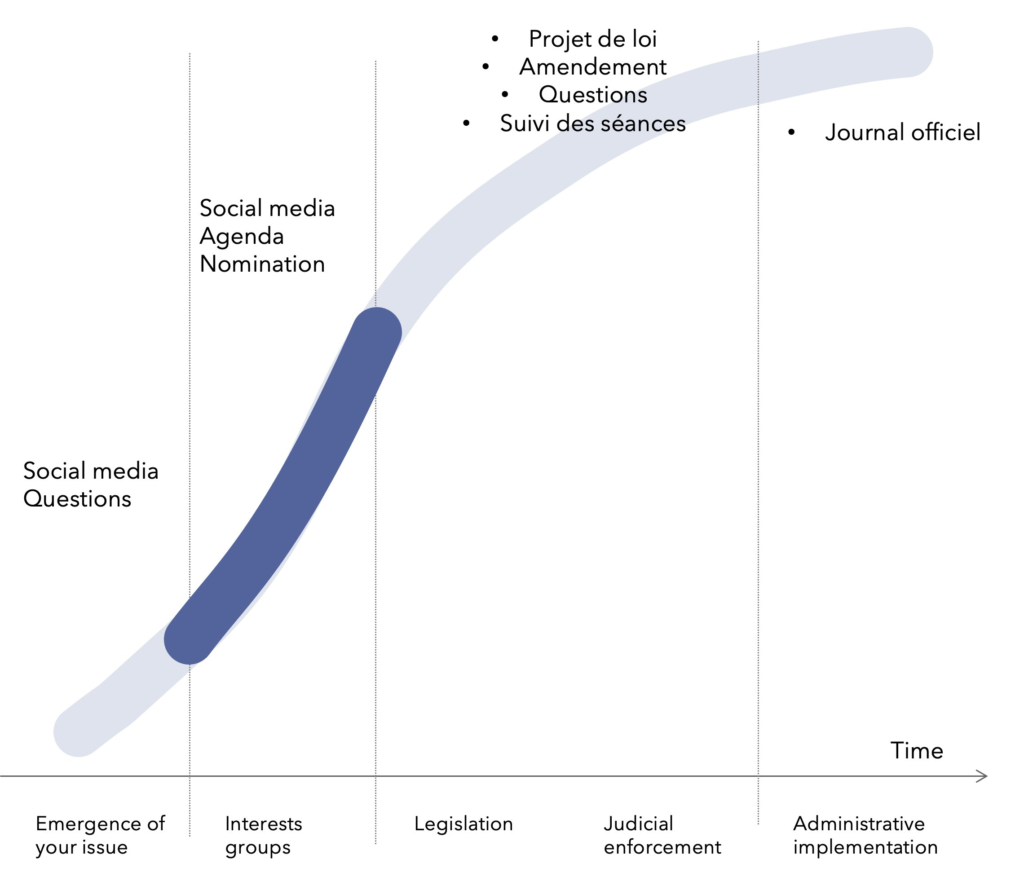

We are clearly at a stage where the problem has emerged and we have moved on to the path of alliances and legislation:

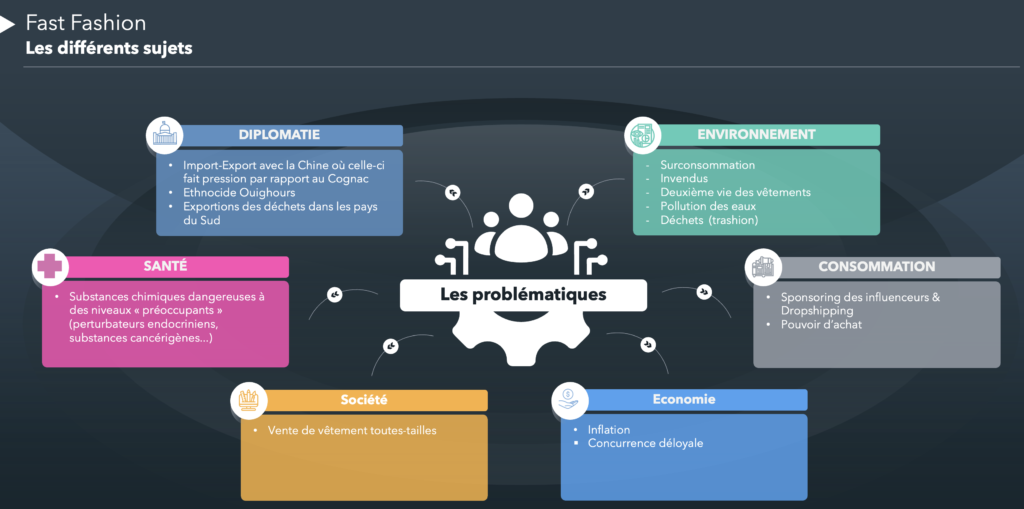

So what's blocking the move to regulation? Many things, including :

A problem of definition : what is fast fashion? Where does it start? You can't make a law for a single player, not for an entire sector. Everything has to be defined. Just the time it takes to establish a definition that is accepted by everyone and that doesn't undermine local players means that there is a delay of 2 to 3 years before potential regulation.

A problem of entry points: as I said in my introduction, fast fashion can be regulated by a whole range of entry points: preventing sales, preventing or limiting promotion, raising compulsory consumer awareness. And each path can benefit all the players in fast fashion, and each has its own arguments. Does fast fashion over-produce? Shein will say that between 100 and 300 items of clothing are produced (which can be increased rapidly if the product is in demand). This prevents unsold items, which account for less than 10% of production, whereas the industry average is around 30%. The company then practices high margins to protect itself from unsold copies. And with so many issues, there are these kinds of power plays and arguments that mean it's not a smooth ride.

A plethora of potential alliances: like every major issue, fast-fashion is capable of activating allies, whether they be governmental (China linking the issue to other export products such as cognac), economic players (the textile industry, influencers, retailers, second life with Vinted, etc.) or interest groups. (It's even possible to imagine other sectors that don't want their communication to be regulated, taking fast-fashion as a case that must not be allowed to go unchecked, or else their solution will become gangrenous).

This is all the more true given that regulation is likely to benefit a minority of players (competitors that are more premium and more "made in France" than Shein), while it will cost a large number of people (purchasing power at half-mast).

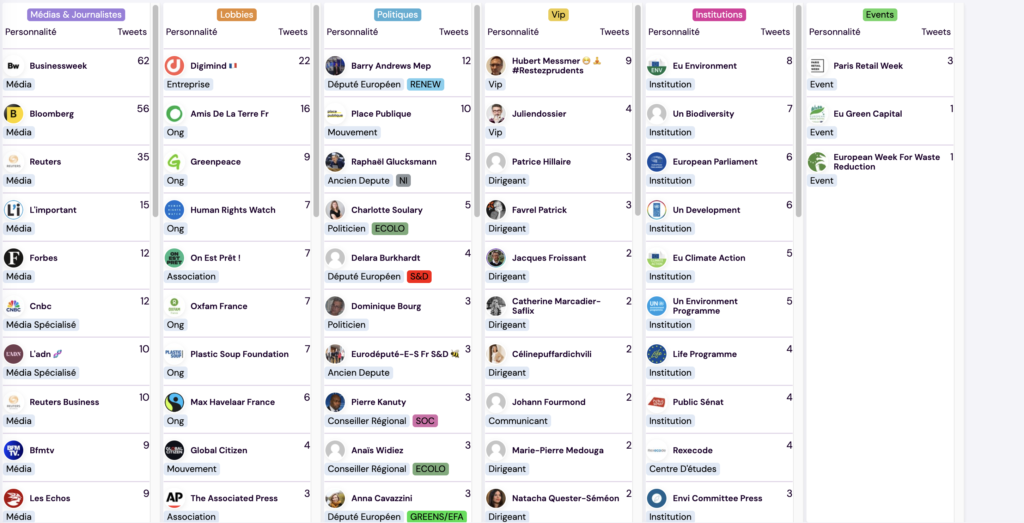

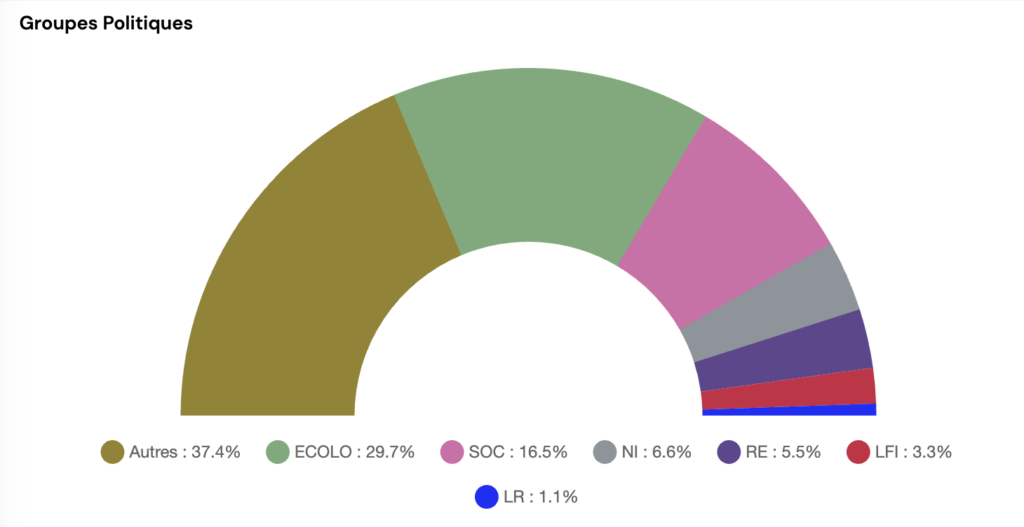

In short, regulators are sure to have a lot of trouble on their hands, with people shouting from all sides and fully mobilising public opinion. In any case, Shein's argument is based on a beautiful 3-cornered billiard table: our less resource-intensive model means that we need less margin. Ecology at the service of purchasing power. Who would have thought it? In any case, Follaw can understand it, if it hadn't foreseen it, given that the stakeholders involved in this issue are very ecological:

An issue typified and embodied by a single political party. Following in the footsteps of the highly environmental stakeholders, the situation is the same at political level, with the issue dominated by the Generation.s - EELV axis. Until now, this has been an essentially ecological issue.

In this case, the law makes an all-out attack on communication, on the Chinese character of the Shein platform, which seems to be clearly targeted, and on the speed of production.

In other words, the draft law is likely to end up at the bottom of Follaw's database until the subject is more clearly defined, the things that can be attacked are better identified, in consultation with the stakeholders and with a political cover other than ecologism in a context where inflation and purchasing power seem to be the priorities of the moment. Or... Until Europe, which is much better equipped to do so, cracks down.

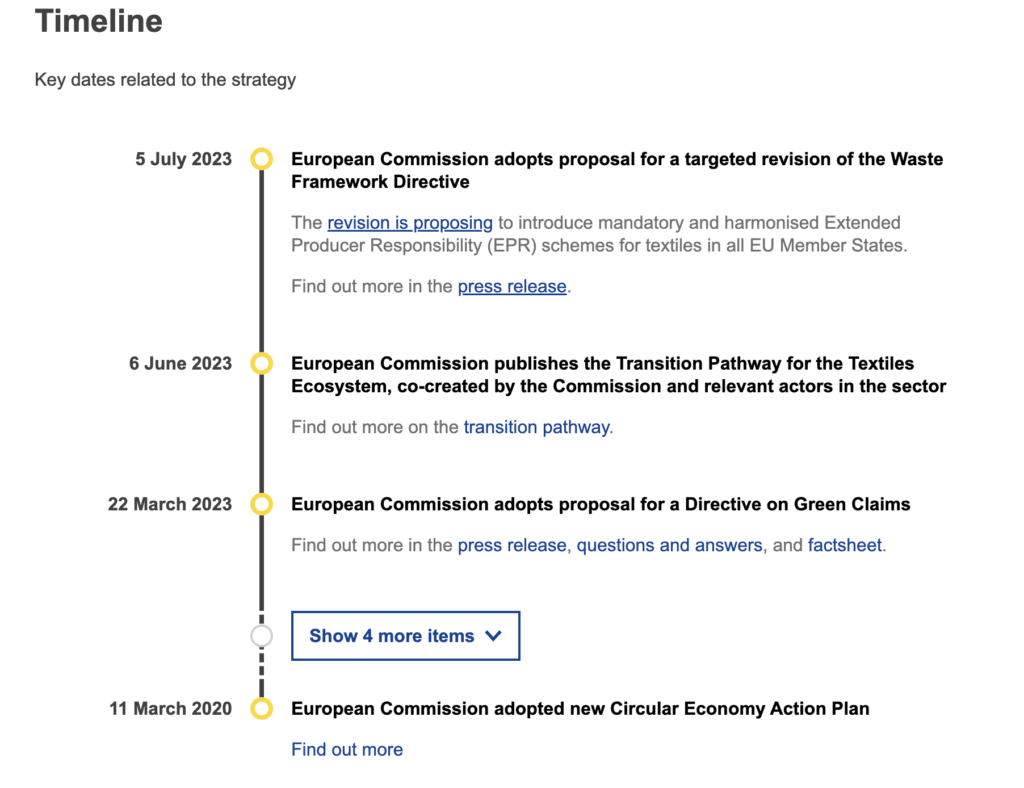

In fact, the European Commission has published its strategy for sustainable and circular textiles, which aims to ensure that by 2030, all textile products placed on the EU market will have a long lifespan, be recyclable and be produced with respect for social rights and the environment.

And so a battle will certainly be waged on this issue. But the challenge now will be to bring together allied stakeholders. And in this respect, there's so much to do!