Sommaire

Employee Advocacy: the unattainable grail of corporate communications?

For some years now, employee advocacy has been presented as the ultimate solution for engaging employees, strengthening the employer brand and increasing companies' organic visibility. This concept, in which employees become ambassadors for an organisation on social networks, holds out the promise of mirabolous positive spin-offs, even though many companies have failed in the past.

Following on from our article on"How to support a manager on social networks", in which we took a straightforward look at the implementation process and the necessary ingredients, I'm going to try and summarise all the notes of intent I've seen and the reasons why they often fall flat on their face. Because behind the promises of an army of enthusiastic ambassadors, the reality is often more complex: team inertia, messages disconnected from authenticity, programmes that run out of steam... The coveted Holy Grail is sometimes transformed into a mirage, leaving communications and HR managers faced with costly initiatives that have little impact. So what's causing these strategies to falter?

I. Why is it a grail?

Let's face it, on paper it's an incredible value proposition:

Large groups have tens of thousands of employees

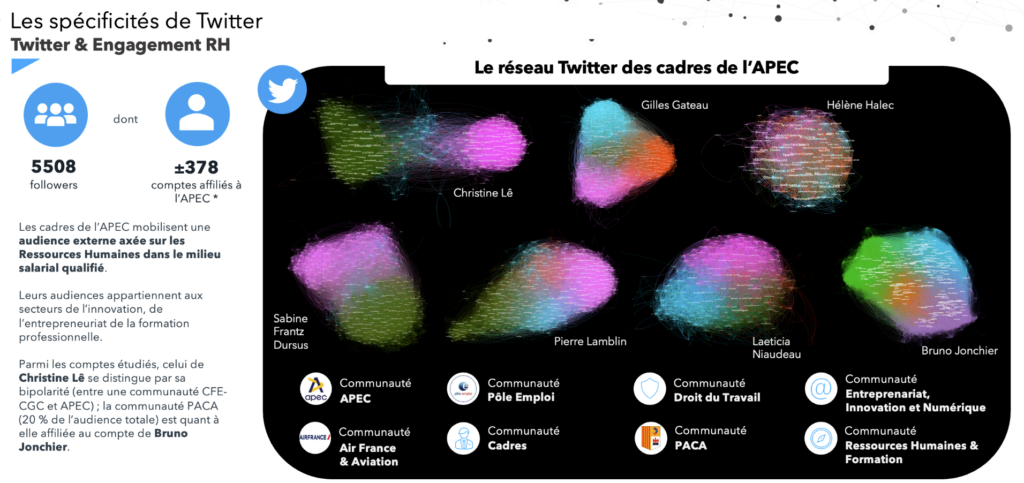

With tens of thousands of employees, large companies have a real asset at their disposal: each member of staff, in theory, represents a valuable asset, an authentic megaphone that can reach circles of trust far beyond traditional advertising campaigns. This is true. As part of a call for tenders for APEC, we identified the networks of each of APEC's executives. And each of them had their own assets, born of their preferred theme, their history and their network.

Together, employees have a much bigger audience than the company, whatever the network.

They can say things that the company cannot

Still in this notion of assets, employees can adopt a tone, a posture and so on that the organisation cannot necessarily embody or say. Because their words fly under the radar of the media and investors, while at the same time reaching out to other employees and other audiences linked to the company's ecosystem.

They are considered more authentic

And lastly, they are considered to be more authentic in that they share an experience that resonates with their background and values with an audience they know perfectly well: their followers or their network.

II. So where does it all go wrong?

And yet, good initiatives can be counted on the fingers of one hand. And one thing is clear: it's more something you surf on than something you create. All the presentations on the subject mention the case of the SNCF, on which it has grafted, but which it did not initiate. This overlooks the fact that not everyone has the potential of the SNCF and certainly does not have the ingredients of this very specific case (especially as the SNCF has grafted more onto initiatives than it has initiated the movement).

Unclear objectives

For a system to work, there has to be a clear objective. Most of the time, there is none other than the existence of the scheme itself. It's easy to say that the objective of a scheme is that it should exist, but for all that, what can you tell the people behind the project?

This lack of objective leads to a lack of ambition, which means that most of the time, the people in charge of the project do not have the necessary position in the organisation to attract a project. How can you attract all the employees to a project if you're below their manager? It's hard enough for a manager to get his team on board. So what about a project manager under a social media manager under a communications director under a chief of staff under a CEO? On the other hand, if the objective is clear, it's possible to sell results to a director and get a mandate from the very top.

This has to be done through the "nonos" that we're going to bring back via the system. ("Through employee communication, I'll help you recruit", "Through employee communication, we'll sell more, which will give you additional resources").

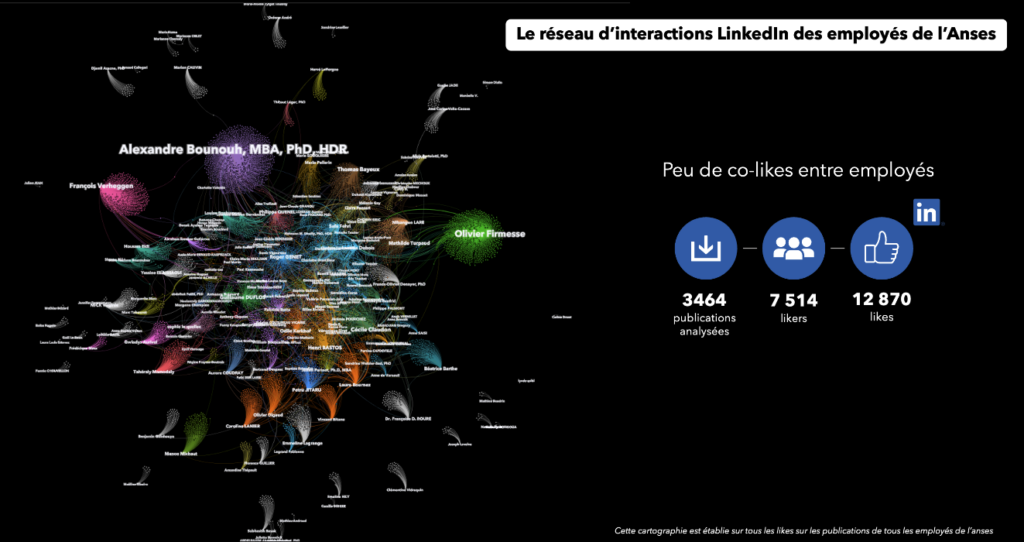

On the other hand, false objectives such as visibility or general commitment do not get through a director's door. Quite simply because these are communication objectives that do not speak to the organisational objectives. What generally remains is the chimera of internal influence from within. "Thanks to the system, you'll be able to talk more to other employees". Let's break this chimera straight away by taking an example that we can make public (but which is an illustration of all the missions for which we have provided objective data), namely Anses. We took the 7514 likers on the employees at the time of this case (2021) to see how they interacted with each other. And what we learned was:

- That the majority of employees are dormant. And even more so about the organisation to which they belong.

- Outside the communications or HR departments, Linkedin interactions are isolated. Each colleague likes each other independently according to their teams.

- On Linkedin, the infrastructure is not conducive to the creation of a community, including one based around working in the same company.

In short, without an objective, the project will die its own death to the sniggering of just about everyone who has seen it.

Watch out for targets

Grassroots employees do not reach the general public unless they are able to create content of interest to them. Most of the time, they only reach people in their profession (because they went to the same school or talk about their profession) or sector (they work on the same things). (So it's unrealistic to think that an engineer from Bouygues Construction is going to reach the general public.

Lack of alignment of interests

The people who initiate these projects often have a total mismatch between the company's expectations and the employees' interests. There has to be a 'shared interest'. But no, an employee won't communicate unless it's in his or her interest to do so. With this in mind, quite a few companies have tried to come up with schemes worthy of the McDonald's of the 90s, such as the employee of the month scheme. The difference is that the good employee at McDonald's knew he was going to become the manager of the restaurant if he carried on like that. Here, it's a competition with no objectives, no bonuses and the dishonour of being the best beaner among a selection of beaners. Models of this type are generally :

- Competition: players compete to win at the same stakes. Is it a good idea to create a rivalry for a system where the aim is to build a coalition?

- Collaboration: the players work together as partners to achieve a goal without reward. Is it good business practice to include people in a no-win, no-lose situation?

- Mutualism: the players have a relationship where each benefits equally from the other. It doesn't work because there is no situation where one employee benefits equally from the other.

The only more objective model is coopetition, a hybrid strategy combining cooperation and competition. An objective is set to be achieved together, and each party will benefit if everyone works together. In this way, interests are aligned.

Apart from this interest, we also need to take away employees' fear of social networks. Because employees understand perfectly well that social networking can be a career hazard. There are no more cases where, as in June 2013, a Taco Bell employee had his photo taken licking Tacos and posted it on Instagram.

But we've all seen the story of the 23-year-old who was sacked for a GIF on the company's What's app:

And there is no shortage of examples of missteps on social networks that result in a strong rebuke.

Organic means organic

Organic means creating interest and authenticity. The perfect metaphor was explained in our previous article, namely that the minute a CEO delegates the writing of his publications to a third party, most of the interest in the publications goes with it, insofar as the authenticity goes.

Not only is someone who only talks about their company no longer authentic, but they will ultimately have no audience. Quite simply because if someone is interested in the company, they will follow it. But no one is interested in someone who only talks about their company. So you need to be selective about your content to get a real angle.

To sum up: the minute an employee becomes a robot repeating the company's words, he loses one of the two assets he has in relation to the company: authenticity. All they have left is their audience. And that audience flees as the editorial line becomes all about the company, and on all kinds of subjects.

Employees log off at the end of the day

If the SNCF has been able to have so many employees active on the networks, it's also because they have train fans among them or people who take the notion of public service to heart.

This passion is not present in all companies and all sectors. The equivalents might be aeroplanes, fashion and beauty, video games, sport, gastronomy, art, culture, politics and, to a lesser extent, law. Outside these sectors, it's hard to find people who can embody a sector outside working hours.

Invisible costs

The invisible costs are often overlooked, i.e. employee time is not free and the entire programme has a cost. Without an objective, as these costs become increasingly visible, the appeal of the project diminishes. They need to be considered in advance, which is not always the case.

III. So we're stopping?

However, this gloomy picture does not mean that an employee advocacy mechanism is impossible. The ingredients seem to me to be :

- Ideally, you should be targeting your own sector and be passionate about it.

- Set a tangible operational objective and find a shared interest with the teams.

- Give employees complete freedom and avoid using the stick if they make a mistake.

- Anticipate the invisible cost.

A good employee advocacy campaign follows these steps:

- Identify what already exists. This involves looking at all the employees who speak authentically today and seeing how they talk about the company.

- Define a collective organisational objective. Include the manager as a close observer of the objective.

- Draw up a to-do not list, the opposite of the to-do list, which sets out problem areas and things not to do. Anything not on the list can be done. The to-do list changes every year.

- Finding a shared interest so that there is something to gain. Obviously, sharing a common goal.

- Aim high at the start because there will be a lot of drop-outs.

- Sharing resources and good practice, while keeping abreast of target indicators to mobilise the whole team. Giving employees total freedom over resources and how they appropriate them.

- Change objectives and participants over time to avoid fatigue.